Los procedimientos almacenados y los sistemas

En seguridad informática siempre se habla de los procedimientos almacenados como un mecanismo para evitar el problema de la inyección de SQL. En What have the STORED PROCEDURES ever done for us? defienden se pueden conseguir ventajas como:

En seguridad informática siempre se habla de los procedimientos almacenados como un mecanismo para evitar el problema de la inyección de SQL. En What have the STORED PROCEDURES ever done for us? defienden se pueden conseguir ventajas como:

Your application is only aware of that one database account that can only execute SP required by your application and nothing more.

That application account can’t access data at all directly.

That application account is created and managed by another database account with a higher level of privileges and that is stored and protected much more securely.

Esto es, el principio del mínimo privilegio.

Además, también beneficios desde el punto de vista de las prestaciones.

Well, this one is easy, everyone knows that at least - STORED PROCEDURES will give you performance gain.

Mantenibilidad, porque nos permiten hacer depuración sin tener que usar el sistema completo.

Execute the STORED PROCEDURE that serves that screen and examine the data. If data contains the bug, then you know that the problem is within the STORED PROCEDURE, if it doesn’t then the bug is somewhere within the application layer.

Disponibilidad, puesto que también nos permiten detectar y corregir determinados problemas en la base de datos.

I may have already mentioned above that you can patch a bug in STORED PROCEDURE without having to stop anything. Hence, availability.

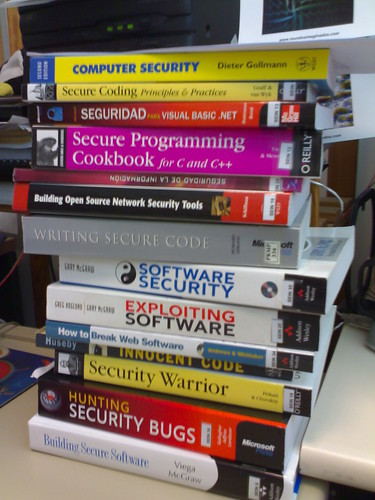

Un recordatorio, presentado de forma llamativa.